Risk Frameworks Beyond ISO 14971 – Why AI Medical Devices Break Traditional Risk Files

ISO 14971 remains the foundation of AI medical device risk frameworks, yet AI medical device risk increasingly stretches beyond traditional ISO 14971 structures. For over two decades, the standard has defined medical device risk management through hazard identification, risk estimation, control implementation and evaluation of residual risk against clinical benefit. That structure continues to underpin CE marking, UKCA marking and global conformity assessment. What artificial intelligence changes is not the need for ISO 14971, but the complexity of the systems being governed.

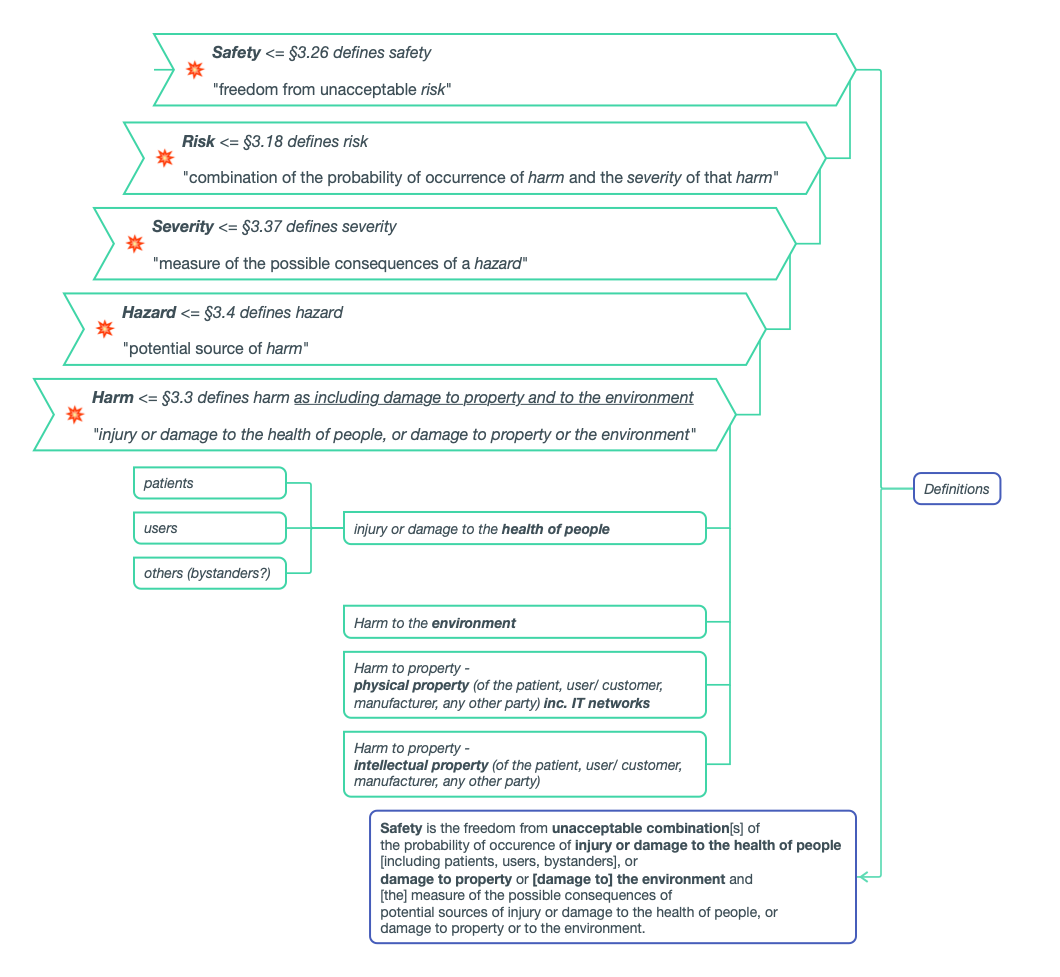

ISO 14971 has been central to medical device risk management for over two decades. It provides a structured and defensible methodology: identify hazards, analyse hazardous situations, estimate and evaluate risk, implement controls, and determine whether residual risk is acceptable in light of clinical benefit.

In my experience working with medical device start-ups - particularly software-centric companies, that structure remains essential. It underpins CE marking, UKCA marking and global conformity assessment. Nothing about AI changes the fact that ISO 14971 is foundational.

However, what we have seen repeatedly over the last few years is that when artificial intelligence enters the clinical pathway, the existing framework often needs to be expanded in practice -not replaced, but stretched.

This blog builds on our earlier one, “What you need to know about risk management for Software as (or in) a Medical Device”, and reflects some of the recurring patterns we, at Hardian Health, see in AI-enabled systems.

AI Does Not Fail Like Traditional Devices

“The problem with AI isn’t that it can be inaccurate - it’s that it can be confidently wrong”

Traditional medical devices usually fail in ways that are visible. Something stops working. An alarm sounds. A parameter moves outside its limit.

AI systems do not necessarily fail like that. They can continue to operate, produce outputs, and appear clinically reasoned -even when performance has drifted.

They are probabilistic by nature. Performance depends on data distributions, training assumptions, and real-world use conditions that evolve over time. In practice, we’ve seen issues arise not because a model “malfunctioned,” but because:

The deployment population differed from the training data

Proxy variables encoded unintended bias (Even if a model does not explicitly use characteristics such as ethnicity or sex, other variables may indirectly reflect them, creating hidden performance disparities.)

Retraining governance was under-specified

Performance degraded gradually and went unnoticed

An AI system can produce outputs that appear clinically reasoned and statistically sound while still being wrong. There may be no obvious system error -only an incorrect prediction delivered with apparent authority.

ISO 14971 absolutely still applies here. But the types of hazards we are analysing are broader, and often more upstream, than many teams initially expect.

Where Most AI Risk Files Fall Short

If you review AI medical device risk documentation today, the structure often looks reassuring:

A conventional ISO 14971 device hazard analysis

A cybersecurity risk assessment

A bias discussion

A post-market monitoring plan

The actual regulatory requirements, such as the UK MDR’s Essential Requirements and the EU MDR’s General Safety and Performance Requirements, directly relating to risk management

On paper, everything appears present- what is often missing is integration.

Instead, you see a 14971 device hazard analysis sitting separately from an ISO/IEC 27001 information security assessment. An NHS DCB 0129 clinical safety case developed in parallel. An EU AI Act section appended later. A PMS plan that does not meaningfully feed into retraining governance.

Each document may be technically defensible. Collectively, they may be structurally incoherent.

And AI risk does not sit neatly inside one standard. It sits at the interfaces - between data and diagnosis, between cybersecurity and clinical outcome, between human oversight and automation bias, between retraining and regulatory status.

When those interfaces are not mapped coherently, the risk architecture becomes fragile - even if every individual document looks compliant.

Machine Learning Introduces Upstream Risk

Guidance such as BS/AAMI 34971 (which supports application of ISO 14971 to machine learning) makes explicit something many teams discover through experience: for ML systems, risk begins earlier.

In practice, some of the most significant safety questions arise during:

Dataset selection and curation

Annotation and ground truth definition

Feature engineering

Retraining governance design

Performance monitoring strategy

A model trained on incomplete or skewed data does not “fail” in the traditional sense. It performs exactly as designed - just not necessarily as assumed.

If risk management effectively begins at deployment, rather than at data provenance and model development, it is often conceptually incomplete.

Autonomy Changes the Risk Equation

Not all AI behaves identically in the clinical pathway. The American Medical Association’s policy on “Augmented Intelligence in Health Care” emphasises that these systems are intended to support -not replace - clinician judgement.

In practice, AI tools can be conceptualised along a spectrum.

Some systems are assistive: they highlight clinically relevant information but leave interpretation entirely to the healthcare professional.

Others are augmentative: they analyse and synthesise data to produce clinically meaningful outputs that inform decision-making.

At the far end are autonomous systems: they interpret data and generate recommendations - sometimes initiating action - with limited human mediation.

As systems become more autonomous, the nature of risk changes. In my experience, teams sometimes assume that “human-in-the-loop” automatically mitigates risk. In reality, automation bias and overreliance can still occur.

ISO 14971 requires that risk controls themselves are assessed for introduced risk. With AI systems, that recursive analysis becomes more nuanced. An override function, for example, may mitigate one harm but introduce workflow or cognitive risks elsewhere.

Cybersecurity Is Now a Safety Issue

For AI medical devices, cybersecurity and patient safety are closely intertwined.

Confidentiality affects trust and legal compliance- once patients or clinicians believe data is not handled securely, adoption drops quickly

Availability affects continuity of care -if a system is offline in the middle of a pathway, clinical workarounds immediately emerge

Integrity directly affects clinical outputs and if inputs are altered or corrupted, the model may still produce a confident result, just not a reliable one

In practice, these are not abstract information security principles; they translate directly into patient safety implications.

If data inputs are corrupted, predictions change; if retraining pipelines are insecure, behaviour shifts and if third-party libraries introduce vulnerabilities, underlying safety assumptions may no longer hold.

Security risks need to be explicitly mapped to patient harm scenarios. Data integrity compromise should appear in the hazard analysis. Retraining governance should be visible within design control and change management processes.

This is where ISO 14971 and ISO/IEC 27001 can no longer operate in parallel silos.

Security risk assessments must explicitly map to patient harm scenarios. Data integrity compromise must appear in the hazard analysis. Retraining governance must be reflected in the change control process within the Medical Device File.

The NHS Context: Governance, Not Just Compliance

In the UK, regulatory approval does not guarantee NHS adoption. AI systems must operate within NHS governance structures that have their own terminology and expectations.

Alignment with DCB 0129 (manufacturer clinical safety case) and DCB 0160 (adopter clinical safety case) is essential. Clinical Safety Officers (CSOs) must be clearly trained, assigned and accountable. Clinical hazard logs must be traceable. Assumptions about deployment environments must be explicit.

If your risk management file does not reference:

The role and accountability of the CSO

Clinical safety case reporting structures

Hazard IDs aligned to NHS methodology

Operational deployment assumptions within NHS IT environments

Interoperability constraints with EHR systems

Postmarket surveillance requirements, both proactive and reactive

Then discussions with NHS trusts become significantly more complex.

The NHS assesses governance maturity as much as regulatory compliance. Your risk architecture must translate seamlessly into NHS language, not require reinterpretation.

The EU AI Act and Lifecycle Risk

The EU AI Act formalises something regulators have been signalling for years: AI systems are dynamic.

If your AI medical device requires a Notified Body under MDR/IVDR - it will also be high-risk under the AI Act. This introduces explicit obligations around data governance, lifecycle risk management, technical documentation traceability and integrated quality management systems.

Risk management therefore becomes longitudinal.

Post-market monitoring must inform retraining governance. Retraining governance must inform regulatory impact assessment. Change control must reflect model evolution. If your risk file reads like a static artefact -frozen at the point of CE marking -it is misaligned with the adaptive system it describes.

One File or Five?

Risk management for AI medical devices must evolve from:

“We have a risk register.” to: “We have an integrated risk architecture.”

That architecture brings together for the total product lifecycle (TPLC) cradle to grave development, deployment and utilisation of a product:

ISO 14971 medical device risk

Machine learning–specific risk (BS/AAMI 34971)

Information security risk (ISO/IEC 27001)

NHS clinical safety requirements

EU AI Act obligations

Post-market surveillance and change control

Not by duplicating hazards across documents, but by designing a coherent framework in which data risk maps to clinical harm, security risk maps to patient impact, retraining maps to regulatory consequence, and post-market evidence feeds continuous risk re-evaluation.

ISO 14971 remains foundational. In my opinion, it is still the right starting point for AI medical device risk management.

What is changing is not the need for the standard - but the complexity of the systems it is being asked to govern.

The organisations we see navigating this most effectively are those that move beyond asking

“Have we completed the risk management file?”

and start asking:

“Is our entire management system coherently structured around risk?”

If your company is developing AI-enabled medical technology and navigating the intersection of medical device regulations, ISO 14971, ISO/IEC 27001, NHS clinical safety frameworks and the EU AI Act, Hardian Health can help. We support organisations in building integrated, regulator-ready risk architectures that align quality, cybersecurity and clinical governance into one coherent system - not just compliant paperwork.